Wilma Wiggins was a little bit weird, but she was definitely not a witch. Despite what they said in town. Yes, she lived alone in the woods in a crooked little cabin and could often be seen stirring a cast iron caldron, but that was for mixing herbs and burning incense. A product of the 1960s, she was all about freedom, running with the wolves, and getting back to nature. There was nothing evil about her. Yes, she did grow a little weed, but that was just for medicinal purposes. Except for the hairy wart on her chin and a few wrinkles, she was actually quite enchanting.

But there were still the rumors. People pointed and called her peculiar, but Wilma liked to think of herself as discerning. An adherent of feng shui, she liked things a certain way and in a certain place to maximize the flow of energy in her surroundings. And Wilma had lots of things—whimsical things—quirky clocks, colorfully painted rocks, angels made of found objects. She even had a fairy garden that she expanded each year, believing it brought good karma. But perhaps the thing that gave people the most pause were the gigantic gnomes surrounding her cabin. Wilma fashioned them from clay, fired them in her kiln, then positioned them like glazed guards around her property. When children went missing or ran away, the townsfolk whispered, wondering if Wilma had turned them into one of her gnomes.

One day, while Wilma was sweeping her front stoop, two disheveled teens approached the cabin. The boy seemed to be dropping something from his pocket every few feet. Wilma didn’t like it when people littered, especially around her house, but she didn’t want to jump to conclusions. She knew what it was like to be judged, and Wilma considered herself open-minded. Having meditated that very morning, she was feeling generous and big-hearted.

“Can I help you,” she asked, putting on her winsome smile.

“We’re lost, old lady,” said the boy, dropping another morsel from his pocket. “And starving. Got anything to eat?”

Despite the boy’s rudeness, Wilma could see that the bedraggled couple were strangers to the forest, so she gave them a pass. “Come in for my homemade kombucha and toast with cactus jelly,” she offered. Wilma was a vegan and grew her own food, so it was the best she could do.

The boy grunted, and the girl rolled her eyes, but they followed her inside. The boy—whose name was Hans or Harry or Hank—mumbled a lot, so Wilma wasn’t sure, and the girl—Gretel, but her friends called her Grace—whined a lot, mostly because the woods had poor Wi-Fi. From what Wilma could gather over lunch, their father had recently remarried, and their “mean” stepmother was forcing them to do chores around the house. In addition, the boy had been limited to one hour of video games a day, and the girl was told to stop dressing like a tart. The stepmother also forbade cell phones at the dinner table. So, they had run away but without a particular destination in mind.

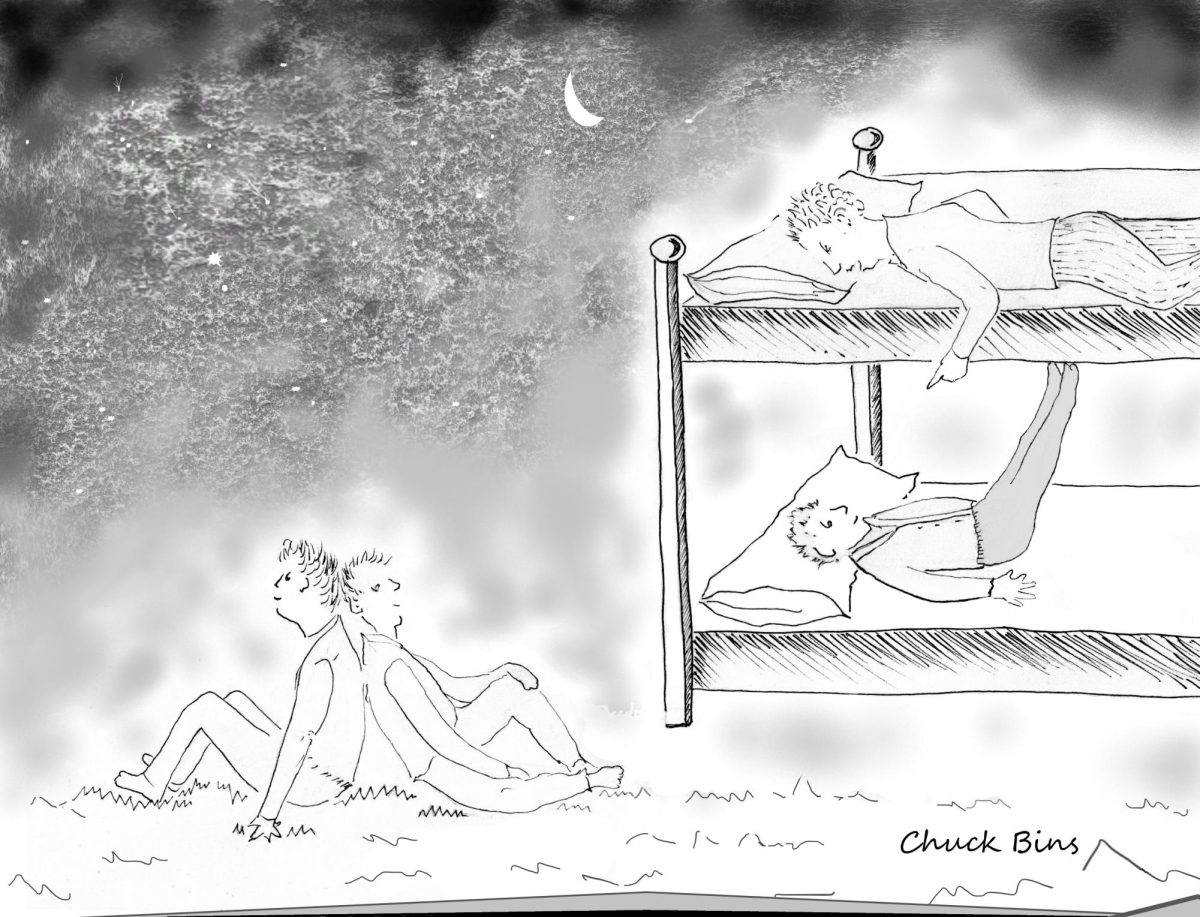

No, they had not thought that far ahead. Nor had they considered the implications of dropping breadcrumbs along a path inhabited by birds and other woodland critters. But Wilma wanted to be charitable, so she didn’t criticize. Instead, she offered them her futon and unrolled a Japanese floor mattress so they could get some rest. After a good night’s sleep, she would lead them back to town.

But the next day, Hank, having discovered Wilma’s marijuana patch, was disinclined to leave. Instead, he spent the next two days camped out back in a musky haze, expounding theories of nonsense about the universe. When his high wore off, he needled Wilma to give him access to the plants. “I know a guy who knows a guy…” he would begin, ending with how he could make them both rich. And Grace, who failed to live up to her pretty name, broke several of Wilma’s curiosities, including an intricately designed twig house in the fairy garden. She also bellyached about Wilma’s lack of decent cosmetics and used the cauldron for facials, every so often popping a zit over the steam.

After a week, Wilma had had enough. She removed her macaw parrot from his cage—the bird was much better behaved than the teens—and put Hank inside so he would not steal from or destroy her garden. She made sure he was sufficiently fed, but every morning she would make him stick out his fingers to make sure they were not covered in weed residue. After all, the cage had a very simple lock, and if the boy weren’t so dim-witted, he would have figured out how to escape.

To keep Grace occupied, Wilma she sat the girl in front of her potter’s wheel and demonstrated how to create and repair items for the kiln. Not feeling quite as charitable as she had a week earlier, Wilma allowed herself a little white lie—telling Grace that the clay mixture would soften her skin and improve her complexion. She really didn’t expect that the girl would smear it all over her face.

Wilma waited and waited. Surely the father and stepmother would be anxious about the disappearance of their children and come searching. But months went by, and nobody came.

Then, about a year later, while Wilma was outside doing yoga, her pet Macaw at her side, a peddler stopped at the front gate. He hesitated at first, mesmerized by the many gnomes, but eventually he turned his cart down the path leading to her house. His wife had recently died, he said, and he was traveling north, trying to find his two runaway children.

Wilma said she lived alone and had not seen anyone for quite a while. It was not exactly a lie, although Wilma could feel her face redden a bit. The old man glanced around her property, obviously searching for the right words.

“I imagine town folk would not fare well in these woods,” he said sadly.

“No,” said Wilma, “probably not. It’s easy to lose your way.”

“Those two gnomes,” the man began nervously, looking back down the path he had come. “They look…”

“Not my best work,” said Wilma, cutting him off. “Maybe you’d like to see others I’ve done.”

“No, it’s just that those two near the entrance, out by your compost pile, remind me of my children. The boy gnome, stretched out on his side, a reed in his mouth, looking lazily into the distance. And the girl, well, she wears an expression that my daughter often exhibited. She was spunky that one,” he said, wistfully.

Wilma thought “insolent” was a better word to describe the girl, but she did not want to be unkind. “Please, please take them, my good man,” she suggested to the peddler. “I have so many, and I’d be happy to have you take those two off my hands.”

The man brightened and tried to give Wilma a gold coin, but she would not accept it. She quickly helped the man load the gnomes onto his wooden cart and waved goodbye.

Wilma returned to her yoga mat and assumed the lotus position. She breathed deeply, taking in the sweet air of the present moment. When she was sure the peddler had turned the bend, she whispered, “Good riddance,” letting a tiny smile escape her lips.

“Good riddance,” the macaw echoed a bit louder. “Good riddance.”

Image by Stefan Schweihofer from Pixabay

Sadie Campbell • Oct 30, 2024 at 1:19 pm

Catchy title! As a lover of gnomes, I was amused by the way Wilma “positioned them like glazed guards around her property”! And the name choice of Wilma was brilliant. Sadie Campbell