On the afternoon of August 15, 1960, a powerful thunderstorm struck the border town of Eagle Pass, Texas, with winds recorded at 110 miles per hour, accompanied by hours of torrential rain. Two towering live oak trees growing above a rocky escarpment near the Rio Grande River were knocked down by the high winds causing the earth beneath the trees to collapse, revealing a cache of Spanish military equipment hidden centuries before.

A combined team of archeologists from the University of Texas and National Autonomous University of Mexico cordoned off the area and set up tarps to protect the site from rain and sun. They also positioned a small gasoline generator to power the intense lights required for excavating.

The residents watched in fascination as the items were catalogued; 23 sets of Castilian armor, 19 metal vests called cuirasses, a crossbow, chain mail sleeves and neckpieces, a chin strap, one harquebus, a rotted leather bag containing over 50 arrowheads with three flint knives, a two-handed sword and three ordinary swords. The broadsword was engraved with the motto, “To uphold the service of God and his Majesty” on its still shiny Toledo steel blade. The storm brought closure for the families of these explorers who’d disappeared more than 400 years before. The scouting column was led by Captain Bernardo Escobar Vazquez from Valencia, Spain. Their intention was to bury their equipment while searching for the main force of explorers, but they never returned. Disease and starvation accomplished what the indigenous warriors had been unable to do.

Bernardo’s diary and a letter to his mother were found wrapped in oil skins inside a sealed clay jar. The diary was preserved in pristine condition. The ink used on the parchment pages looked as if the beautifully scripted sentences had just been written. The chief archeologist and her translator could not help but read a portion of Bernardo’s letter to his mother before replacing it in its sealed container:

December 25, 1545, “…I have had the honor to cast my eyes on the wonders that God has created in other worlds different from ours. The plants and animals are like no others near our home in Valencia: rabbits with ears as tall as they are long, wild pigs that look fierce but the taste of their flesh is heavenly, and a large speckled bird that stays with travelers and warns them of dangers—we call it paisano or Holy bird because they have four toes on each foot; two face forward, and two face backward forming a sign of the cross—and a thousand varieties of cactus. This must be the place where the Ark settled after the great flood because every day I see a new species of reptile, fish, mammal, bird, and insect. This is truly a land of extremes, with high mountains, deep canyons, deserts, and forests. If only I could have had you and father by my side when we surveyed the tall plateaus, where the land seemed to stretch for hundreds of miles. We have been hindered by those who went before us. They did not seek the natural wonders of this new world but pursued a path for glory and gold. We set out on the same route that the conquistadores pioneered. We had ample supplies for our group of 50 men and 100 horses. Five years before, our predecessors attacked the indigenous villages, pillaging, murdering, and commandeering food, supplies, and captives. We suffered greatly from the revenge that followed, but fought our way east, until our supplies and men were exhausted. We have accepted that our mission was a failure for we will return, God willing, to our base near the river we call the Rio Bravo, with no gold, no silver, and no established colony, having only hardened the antagonism of the native peoples. I hope to return to this place some day and bring you and father with me. This is a lonely time for being away from you both during Christmas but someday, God willing, the three of us shall celebrate this Holy season together in the New World. Many who arrived here with me returned early to Spain, disappointed in their quest for glory and wealth. The riches of this country are not found only in its minerals but exist in the unique flora, fauna and in the innocent hearts of its native peoples. Merry Christmas to all, your obedient son, Bernardo.”

Captain Bernardo Escobar Vazquez never saw his beloved Valencia, Spain, or his parents again. He succumbed to a brutal outbreak of an unknown gut bacteria epidemic in 1546 that killed between five and 15 million alone—up to 80 percent of the population. But, like the other epidemics, the disease behind the 1545 outbreak was a complete mystery—until now.

Genetic evidence pulled from the teeth of 10 victims suggests that the bacterium Salmonella enterica contributed to the scourge of fever, bleeding, dysentery, and red rashes recorded at the time. The genetic data, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, offers the first molecular evidence to explain what’s “regarded as one of the most devastating epidemics in New World history.” Captain Bernardo Escobar Vazquez’s Christmas letter allows us to glimpse the past through the eyes of an explorer, naturalist, and essayist.

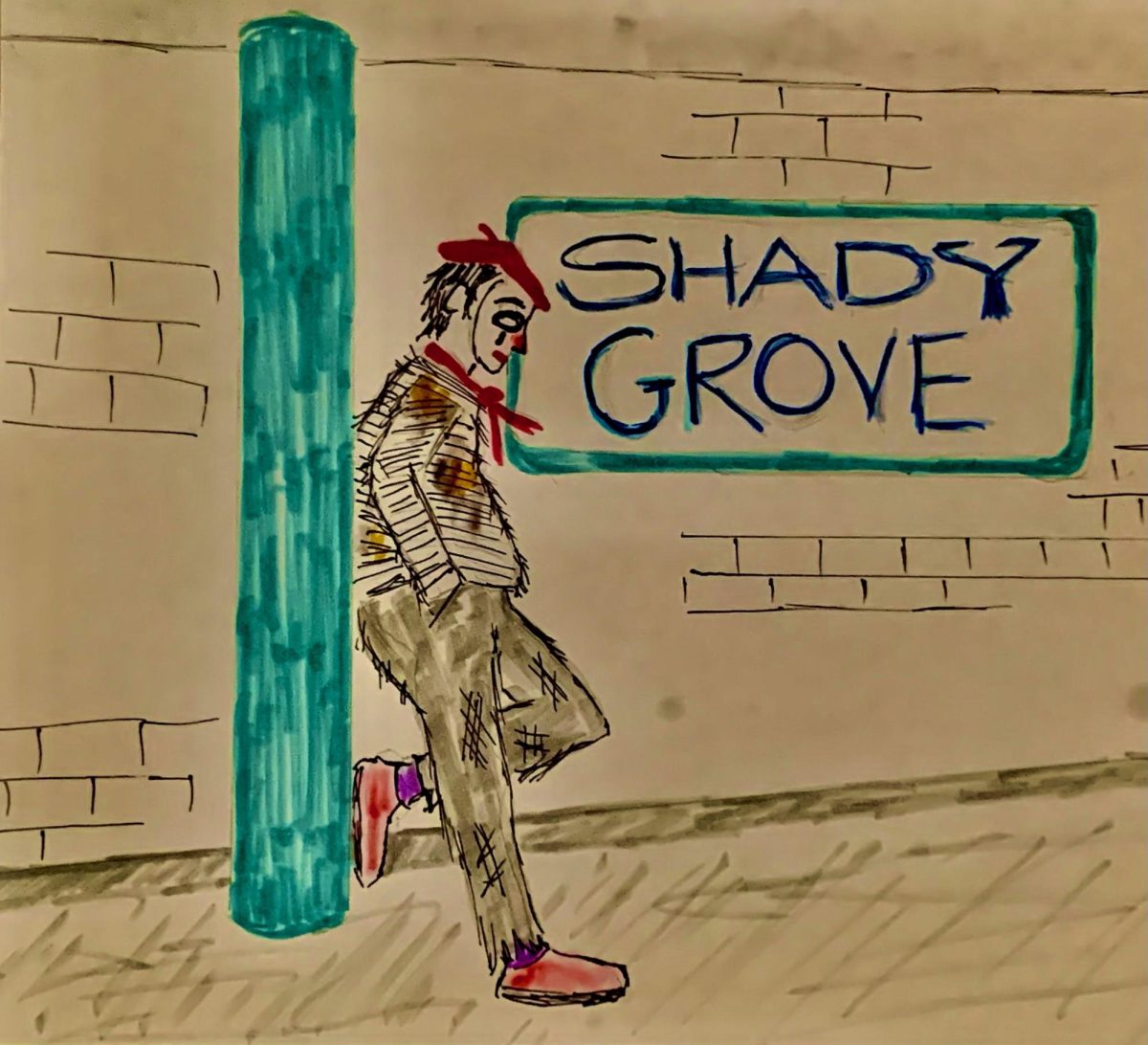

Merry Christmas to All