Today, genocide is an internationally recognized crime where acts are committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. These acts fall into five categories:

Act I – Killing members of the group.

Act II – Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group.

Act III – Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.

Act IV – Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.

Act V – Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

***

In the early 16th century, there were no prohibitions against genocide. It was looked at by many of the European explorers in the Americas as a necessary clearing of indigenous people like clearing of brush and vegetation to make room for adequate housing for Europeans. Today, many nations feel the same way about ecocide, the destruction of the natural environment by deliberate or negligent human action. It is hoped that those who occupy the Earth will become more aware of their responsibilities for environmental stewardship. And now, we regress to the mid-16th century and the European conquest of the New World for God, gold, and glory.

***

Juan Alvarez had served the Spanish Crown for eighteen years as one of its most reliable military commanders in the New World. After Hernan Cortes had overthrown the Aztec empire in 1521, Spain began to expand its influence in its western colony. Alvarez led expeditions that established the port cities of Veracruz and Campeche. But now, he’d been ordered northward. It was July of 1545, and a massive vein of silver had been discovered near the north-central town of Zacatecas. Silver mining became the financial engine that drove the economy of New Spain and created the first global economy. Soon, the Manila Galleons linked Spain’s colonies in the Philippines and the Chinese Empire, making two round-trip voyages a year across the Pacific between the ports of Acapulco and Manila. The Chinese had an unquenchable thirst for silver and the Spanish merchants could not get enough Chinese silk, used to supply the new European markets. Fashion and commercial finance now directed military objectives. Alvarez became the Captain-General of the Spanish garrison in Zacatecas, but the city and its surrounding forts and silver mines sat in the middle of land claimed by a force of 60,000 nomadic Chichimeca native peoples. They referred to themselves as Children of the Wind and considered their land sacred. The Spaniards were intrigued by the Chichimeca; their men and women wore little clothing, grew their hair long, and painted their bodies. At first, the aloof Chichimecas were considered noble savages; wild sub-humans who could be cruel and crafty.

The discovery of rich deposits of silver caused many Spaniards to emigrate from southern Mexico and Europe to Zacatecas. The Chichimeca nations resented the intrusions on their sovereign ancestral lands by the Spanish. Spanish soldiers, acting as mercenaries for the wealthy landowners, began raiding Chichimeca villages to acquire slaves for the mines. This is when the Spanish discovered the reason why the Aztecs left the Chichimecas alone. They were the fiercest and most ruthless warriors in Mexico. The caravans of silver bound for Acapulco and the inbound convoys of silk became targets for Chichimeca warriors. Bars of silver bullion were thrown into rivers and bolts of finely brocaded silk were burned or shredded. Captain-General Alvarez faced the pressure of the merchants, clergy, and their allies in the Spanish royal court to find a solution. Alvarez’s losses mounted. No matter how many lancers and foot soldiers he deployed, the Chichimeca warriors appeared to be everywhere and nowhere. The army’s weapons of broadswords, rapiers, lances, crossbows, and matchlocks proved useless against the hit and run tactics of the Chichimeca. Alvarez would rely upon the assistance of a man who had proven his worth by destroying the marauding bands of Aztecs after Cortes had taken Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire.

“Bring me the Moor,” Alvarez commanded one of his aides. In a few moments, a man dressed in heavily brocaded multi-colored robes with a thick beard and prominent nose was escorted into Alvarez’s office. He made a low bow and rose, with his right hand brushing his forehead. “Salaam; my general,” he said in a voice just above a whisper, “I am, as always, at your service.”

The Moor may have been viewed as a Godsend by Alvarez, but to his senior officers and soldiers, he was a pampered infidel who attached himself to the military troop like a member of the high nobility. His possessions and collection of tents and furniture were carried in an oversized wagon that resembled a small house on ten-foot diameter wooden-spoked wheels.

Brightly colored circles depicting the twelve, thirty-degree divisions of the Zodiac were painted on its side, and garlands of braided garlic hung from the structure’s eves to ward-off evil spirits.

It was drawn by six oxen that caused delays in the army’s ability to move quickly. A company of cavalry was assigned to escort the king’s coach, as the soldiers laughingly referred to it. Others used more profane terms.

“He’s no Moor,” growled one of the soldiers. “He’s too light skinned to be a Moor. He’s a Saracen, a follower of the false prophet, the antichrist!” “He’s attached himself to our commanders like a leech,” said another soldier. “He’s a magician. One of my friends said he’d transformed a Mayan warrior into a salamander!” But the mysterious man was neither trained in the black arts nor was he a Moor or a Saracen. He was an Italian, a gifted actor in a theatrical troupe who’d been captured by the Saracen army during a trip the group had made to North Africa. He was imprisoned as a spy where he was physically abused. Then one of the Caliphate’s physicians took pity on him and had him released to his custody. This was the beginning of his initiation into a profession where his acting abilities would fit well. His mentor was a pioneer in a type of warfare that was neither popular nor accepted by many. It was the secretive use against one’s enemy of naturally occurring substances obtained from plants, reptiles, fish, and animals.

As early as 1200 BC, the Hittites, ancestors of the Assyrians, experimented with biological warfare. Historians reported that Hittite commanders had driven victims of tularemia, rabbit fever, into enemy lands, causing epidemics. The Assyrians also had knowledge of ergot, a parasitic fungus of rye which produced seizures, diarrhea, and something called dry gangrene that resulted in the sloughing off of fingers, feet, and toes. For most military commanders, this type of biological warfare had the same status as the Black Arts did with the Christian religion.

The Italian actor became an adept student and collected over fifty samples of toxins for his use. Soon after the death of his mentor, he and another prisoner escaped after he poisoned the guards and administrators mixing fifty grams of arsenic in the common water cask used for administrators and guard’s meals. The Italian and the two leather trunks that contained his laboratory equipment crossed the narrow straights heading for Spain by boat. He and his baggage arrived at the port of Palos in southwestern Spain with a few gold coins he’d taken from the prison’s strong box. Although he was finally free of his North African prison, he had no prospects of employment. After a few weeks of making the rounds of taverns inhabited by military men and those looking for passage to America, he was recruited as a physician for the army’s New World adventures, and he never looked back. Based on his prison experience, he reinvented himself with a theatrical flair as a mysterious Moor.

***

Alvarez dismissed his aides and bodyguards. He wanted to speak openly about a subject he found repugnant, but necessary. “My friend, I am fighting ghosts, these Chichimeca bandits. They are not affected by our weapons or mounted troops. Do you have a solution for me?” “Describe their lifestyle,” the Moor answered. “Where are their wells? What do they eat?

Where are their cities?”

Alvarez called for one of his scouts who had lived in the area for twenty years. But his answers to the Moor’s questions were not what he wanted to hear. The scout described the Chichimeca as hunter-gatherers who were skilled in the martial arts. They roamed an area that covered 62,000 square miles and did not live in cities. Their diet consisted of wild game, roots, and berries. Their favorites were mesquite beans, edible parts of the agave plants, and the oblong cactus fruit, called tunas, and its flat leaves. They also used the tunas as a source of water. They had no wells, but a few grew corn that would be planted and returned to after it matured. Unlike the Aztecs and the Maya who maintained centralized population centers with sophisticated infrastructures that housed thousands, the Chichimeca lifestyle was simple. “It is unfortunate that these savages do not use common wells,” the Moor grumbled, “My choice for their extermination would have been arsenic. It is odorless, colorless, tasteless, and lethal.”

But the Moor had another idea.

“How many of your soldiers are afflicted with the French disease?” “About twenty,” replied Alvarez.

“Are they being treated?”

“No,” Alvarez replied with a frown, “The army physician began applying mercury to combat the sores and abscesses, but the cure was worse than the disease. We lost six men and I decided to stop the treatment.”

“Ah,” the Moor smiled, “A night with Venus, and a lifetime with mercury! But this is what I want you to do…”

During the next raid for slaves to work the silver mines, the soldiers captured fifteen young women who were brought to the garrison. Each was subjected to forced relations with soldiers affected by the French disease that would become known as syphilis. After a week, the women were returned to the wild where they had been captured. But the expected results of wiping out the rampaging Chichimeca with a sexually transmitted plague never happened. The young women who had been despoiled by the Spanish soldiers were considered anathema and sent into exile.

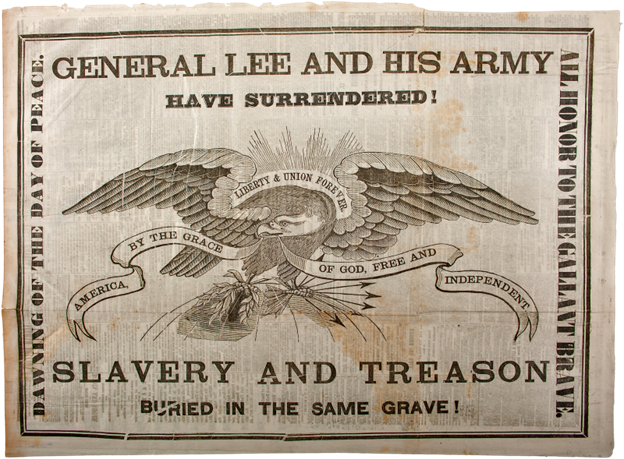

The Chichimeca were finally subdued, but not by military force or the Moor’s introduction of poisons or sexually transmitted diseases. It was by assimilation. Their raids on the commercial convoys had been effective. To end the attacks, the Spanish Crown purchased peace. The Chichimeca observed the flood of settlers and realized that their wandering days were over. The once proud, independent tribes were simply bought off with tools, livestock, and land. And within a century, Christianity and cholera accomplished what the Crown’s soldiers could not; the Chichimeca became another group of the faceless serfs in New Spain, robbed of their culture and pride.

Chuck Bins • Jan 5, 2024 at 10:17 am

Thank you for this dramatic and insightful view into history — a compelling lesson.