The alchemist sat at his worktable surrounded by flasks, beakers, and a marble mortar and pestle he used to prepare medicinal ointments. Behind him was a wooden stand containing glass jars of dried flowers, fungi, and herbs. In the center of his table beside a terracotta oil lamp sat a piece of polished Baltic amber about the size of an orange he’d purchased from a Phoenician trader. It contained a small locust and two black ants trapped in a pine tree’s resin thousands of years before. The locust, with its wings folded behind its body, stared out from its transparent tomb. Its red, compound eyes, sought, but could not find a way to escape.

The alchemist spent hours imagining how the locust was attracted to the pine tree’s oozing sap after a nine-year hiatus underground and had landed in a pool of the pine’s viscous liquid. The harder the locust fought, the deeper it sank. The ants’ antennae picked up the vibrations of the struggle and they instinctively scurried toward their meal, only to become entangled in the same trap. He was intrigued by the insects frozen in time as they stared out of their transparent tomb, unaware that tomorrow would never come.

The alchemist had been asked by the king’s regional administrator to investigate the mysterious deaths in a village located on the Euphrates River. Witnesses described the villagers’ symptoms as convulsions, large open sores, and blackened fingers and toes. Others attributed the deaths of the villagers to sorcery, but the witnesses agreed on one point; all the dead had exhibited hallucinations before death arrived.

Laid out in front of him were sealed glass jars containing samples of rye seeds obtained from fifteen different villages. Some of the seeds appeared swollen and larger than normal; a few had turned a purplish-black color. These were from the village where the deaths occurred. The samples in the other jars looked like common rye seeds. A few days later he observed a mass of black, threadlike filaments sprouting from the purplish-black seeds he’d isolated. It appeared to be a type of fungus he’d heard about but had never seen. He’d identified the effects of the disease. Now he had a possible cause.

The alchemist began to assemble the witness statements for his final report to the regional administrator. He bound his reports together in a leather case and gathered samples of the healthy and infested grains. Then he set off for the regional administrator’s offices in the capital to present his findings.

It wouldn’t be until the 18th century that Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus would create the hierarchical system of grouping animals and plants using Latin and Greek, the international language used by scientists at that time. The rye fungus observed by the alchemist in 310 BC, would become known as ergot, Claviceps Purpurea. The effects he carefully documented would be known as ergotism; ergot poisoning, that would eventually kill thousands.

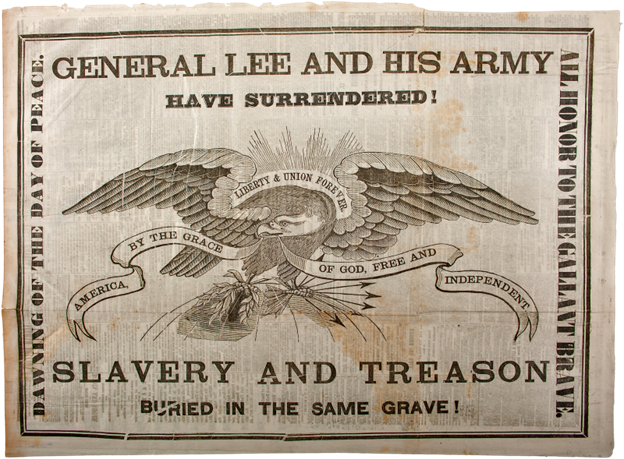

The identification of the chemical culprit that had caused the bizarre behaviors of the sick and dying in the Assyrian village remained a mystery for more than a millennium. In 1938, a Swiss scientist isolated the ergot alkaloids and found that they included lysergic acid diethylamide, known today by its initials, LSD.

Biological science was emerging from the traditions of ancient Middle Eastern medicine and the works of Aristotle; it was in its infancy. The Assyrian alchemist was developing the scientific methods that would be commonplace in the future. It wasn’t just the evolving scientific community that was interested in his work. One man’s plague would become another man’s power.

The Janus-faced nature of science, its constructive and destructive sides, had shown itself. Man’s ability to reason, analyze, and create supposedly separated humans from beasts. The advancement of the sciences of biology and chemistry was linked directly to this ability. But its darker side would produce horrific deaths in equal measure to its advances.

Centuries later, an event referred to as the Columbian Exchange occurred in 1493. The widespread transfer of plants, animals, technology, and ideas between the Old World and the Americas accelerated technological and scientific advances never thought possible in the previous fourteen centuries. Science became formalized and its branches of biology, chemistry, and physics began to evolve.

However, there was a downside to the Columbian Exchange. It was an unintended consequence of the explorer’s fervor to find a western route to India and the spice trade. The crews aboard Columbus’ ships were not the only ones to land in North America. Invasive species and communicable diseases also made the trip to the New World. The focus of the Old World’s political, economic, and military goals shifted. Conquest in the name of God and the seizure and subjugation of the new territories were made for king and country.

Mankind’s ingenuity to invent more efficient ways of eliminating their enemies put an end to the debate of whether humans had a natural capacity to kill other humans. As a way to accomplish the goals of territorial conquest, it was helpful to consider those eliminated as evil, subhuman chattels useful only for their labor. This philosophy would eventually seep into modern warfare, but for now, the noble causes of the explorers’ quests justified their actions. In a few cases, scientists began to pry open the lid of a jar Pandora had filled with strife, sickness, treachery, and death. It was 1519, and the stirring motto of the Conquistadores was, “For God and Country.” The mention of God was necessary. Hell was about to arrive in the New World.

John Turner • Feb 5, 2024 at 12:07 pm

One thing for sure…..human behavior has been very consistent…….regardless of the time or place.

When one accepts that premise………it’s fairly easy to predict the future.

Prepare accordingly!

John Turner

Roanoke, VA