My grandmother “held court” from her rocking chair, regaling her grandchildren with tales of men’s chivalry and gallantry, of ladies’ integrity and dignity. We listened to her stories, spellbound by every word. One tale of yore grandmother repeated concerned her visit as a young girl with Miss Olivia Floyd at Rose Hill, an architecturally distinctive 18th century Southern Maryland plantation mansion built for the father of Dr. Gustavus Brown, a physician to George Washington. Inherited by Miss Floyd’s family, Rose Hill, situated on a high bluff, enjoyed, as it does today, an expansive view of Port Tobacco Creek flowing into the Potomac River.

On January 22, 1900, my grandmother and a girlfriend arrived at Rose Hill at the invitation of Miss Floyd. Grandmother said, “Miss Floyd never married, was old and bent, but still exhibited a keen intellect and recounted fascinating escapades of her earlier life as a spy and blockade runner for the Confederacy during the American Civil War.” She mesmerized her young visitors with anecdotes of smuggling currency, clothing, and information between Union and Confederate lines to assist Confederate prisoners. One adventure involved Bennett H. Young of the Confederate Army who conducted a celebrated raid at Saint Albans, Vermont, to deflect Union troops from skirmishes in the southern states. Afterward Young fled and was later captured with his men in Canada. To avoid extradition and trial by federal authorities, Young needed proof of his Confederate Army commission from President Jefferson Davis in Richmond, Virginia. In the winter of 1864, Miss Floyd prevented Union soldiers from finding those smuggled necessary papers to save Bennett Young and his men from being hung as guerilla irregulars.

Grandmother remembered Miss Floyd’s animated conversation as she sat beside a large open fireplace. Huge logs crackled behind shiny brass andirons, lighting the room with a golden glow. It was those brass ball-top andirons where Miss Floyd hid documents from the Yankees. A servant helped unscrew the tops, Miss Floyd wrapped the important papers inside the andirons, and they screwed back the tops. Yankee soldiers arrived as expected, questioning Miss Floyd about her return to Rose Hill from Virginia across the river. Miss Floyd offered the soldiers food and drinks. They searched her home, sat by the fire with their boots on those andirons, and left without finding any concealed documents. Grandmother added, “Yes, those Yankees didn’t find anything except Miss Floyd’s charming hospitality.” After tea, Miss Floyd thrilled the young girls by reading their fortunes and giving them her autographed photograph.

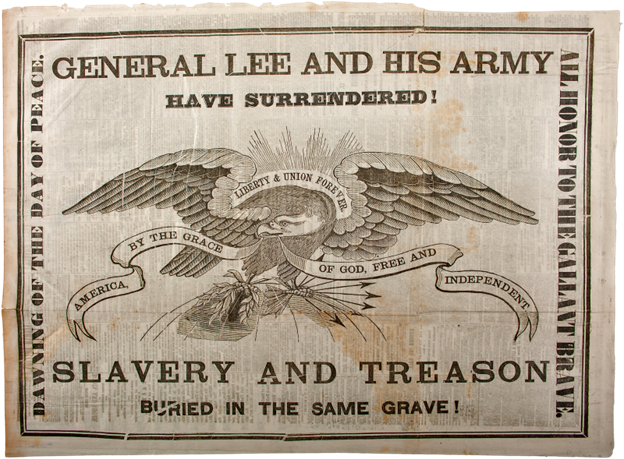

Southern Maryland, with its tobacco growing slave economy, tended to side with the Confederacy while much of the state supported the Union. President Lincoln activated about 75,000 state militiamen for the Union. By May 1861, Union troops occupied Maryland, preventing a vote in favor of secession. Known Maryland Confederate sympathizers fled the state to avoid arrest, with about 25,000 former members of the state’s militia joining the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Some remaining women took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union for protection of their families, homes, and livelihood. As able-bodied freemen fled, President Lincoln’s men conscripted Southern Maryland male slaves into the Union Army, leaving many homes abandoned to women and children. Married and elderly women were tasked with raising children and running the household. Young unmarried women like Miss Floyd, whose brothers, fathers, or relatives were killed in combat, volunteered, or were recruited to help the Confederacy.

Miss Floyd, an attractive, intelligent, ardent secessionist, acted as an operative, passing vital documents between couriers while evading her arrest. Some years after the war, Miss Floyd, invited by Colonel Young, was honored for her services at a Confederate Reunion in Kentucky where attendees reminisced and exchanged stories with a heroine of The Lost Cause.