One of the fundamental principles of our founding documents is that we Americans don’t kowtow to anyone claiming privilege on the basis of parentage. We’re not subjects, we’re citizens, we don’t have fiefdoms, we have states, roles in our government are not inherited they are earned via the vote. But that’s not to say that we don’t have our royalty; we do. We have a Count, a Duke and an undisputed King of Jazz in Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and the irrepressible Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong. In his new book, “The Jazz Men,” journalist Larry Tye tells the much-needed story of these men, warts and all, but with great appreciate for their craft and, perhaps more importantly, for their times. These men were not just musical pioneers, but cultural pioneers as well. Tye celebrates the two.

The first concert I ever went to was, as a young wanna’ be trumpeter with my best band friend and his private trumpet teacher, at Pittsburgh’s magnificent Syrian Mosque (now a parking lot) to hear Satchmo himself. My first concert to hear my first musical hero. I was fifteen years old and the evening was beyond magical, especially when Mr. Pasquerelli, the teacher, escorted us into Mr. Armstrong’s dressing room after the concert to say hello. I felt like I was in the presence of a king and, in fact, I was. Some years later I was playing on weekends with a band while in the army in Germany and we were asked to go on an USO tour for the holiday season. That brought us into contact with several other musical groups, This was the late 60s and civil rights was a hot issue, even though all of our groups were integrated. What surprised me the most among my new found African American friends was their opinion of Armstrong as an “Uncle Tom.” That generation, my generation, was angry, was determined to see racial attitudes change and saw Satchmo as a facilitator to the old establishment of Blacks being held in second-class status.

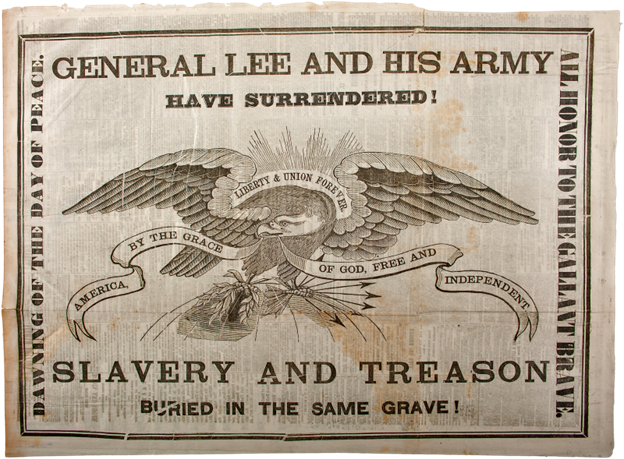

They couldn’t have been more wrong. Armstrong was a pioneer in race relations, but he did it mostly through the brilliance of his horn. He invented the voice of Jazz and broke through all of the Jim Crow stereotypes of his time. His fans were completely interracial and international. And when war hero President Eisenhower dithered over sending troops to integrate some southern schools, he called the winner of World War Two a “coward.” Some “Uncle Tom.” But the jazz men of my generation weren’t aware of the courage that it took for a man of those times.

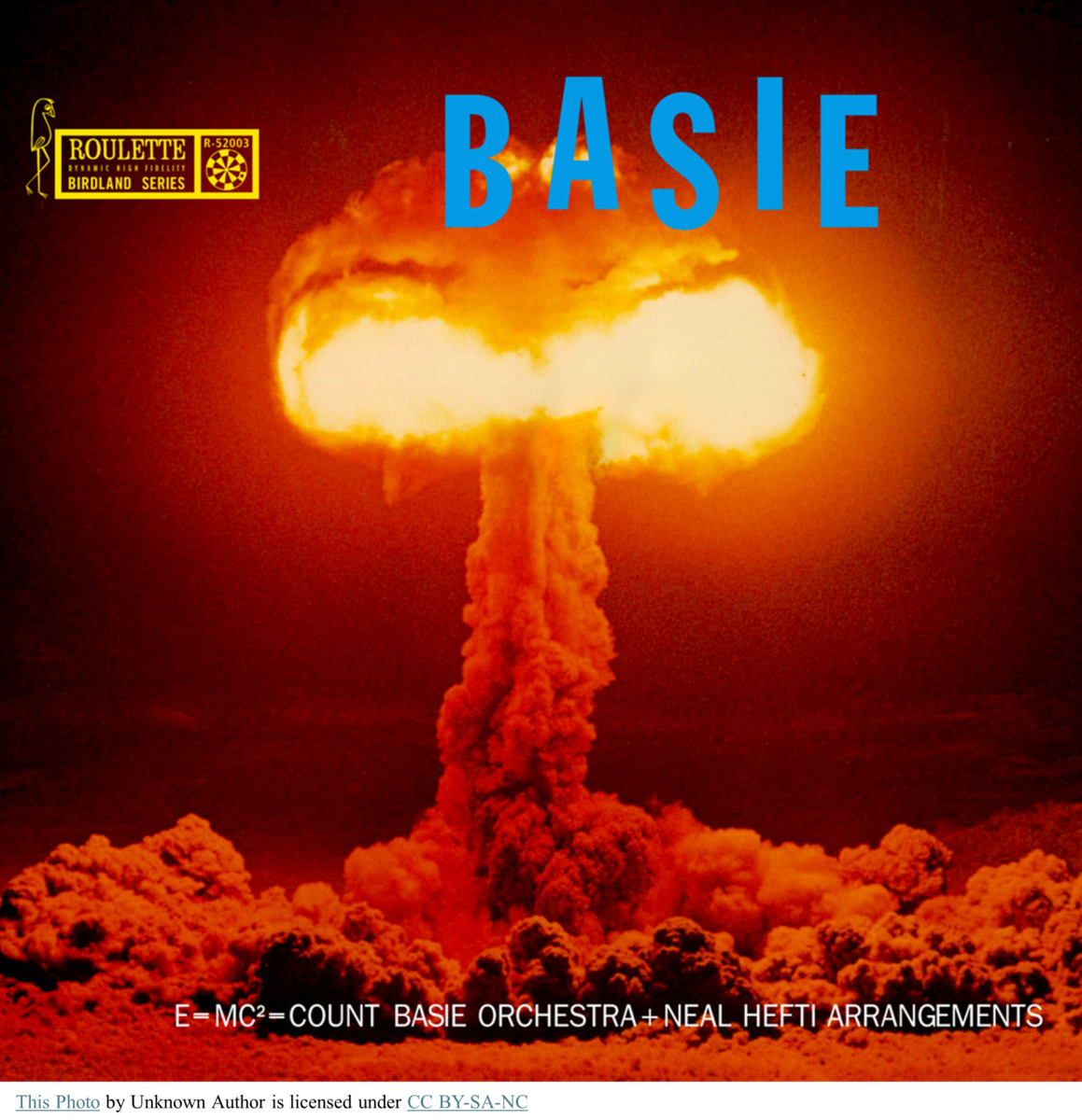

Meanwhile, Ellington and Basie also broke barriers. As Tye points out, people at that time who wouldn’t stay on the same side of the street with an African American bought their records, danced to their tunes, and wooed their lovers with their music. You couldn’t listen to Basie and not tap your foot or be amazed by some of the exceptional soloing in all sections of his band. And Ellington stood out as much for his refined dignity as for the sophistication of his music. They were the true pioneers in that movement.

Read Mr. Tye’s book. We’ve made progress in our society thanks to our royalty.

Timothy F. O’Connor • Jun 5, 2024 at 9:47 pm

Paul, thank you once again for sharing your experiences.

I greatly appreciate your insights and eloquence in writing as well

Gary Cassady • Jun 3, 2024 at 5:56 pm

Really. Nice read Paul. You did a great job on this.