Twice annually, snowbirds vacate their seasonal habitat, escaping cold winters and hot summers as they migrate to their desired locations. Like the California swallows of San Juan Capistrano who depart each October 23rd and return each March 19th, other snowbirds seem as exact with their schedules, barring an unfavorable weather event.

Sandhill Cranes, whose name is derived from Nebraska’s Sandhills of the Great Plains, and their subspecies, are distinctive large birds, standing three to four feet tall, with wing spans of five feet or more. They can be identified by their long, thin necks and legs, white cheeks, a bright red crown and gray feathers. Their diet is mostly plant based. When mature, sandhill cranes weigh between seven and eleven pounds. These impressive birds reside in scattered regions of North America, preferring prairies, fields, marshes, wet grasslands, river basins, and tundra.

Three subpopulations of sandhill cranes migrate: the lesser, greater, and Canadian, each spending summers at their annual breeding sites, and winters in California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico. The largest migrating population of sandhill cranes can be observed from February to early April along the Platte River in Nebraska. During spring months, they can be spotted feeding and resting along water courses of the Great Plains and Pacific Northwest as they migrate to their summer breeding areas of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, and others in Oregon, Idaho and Alaska. The nesting couple raises one or two chicks, with the male guarding the nest built on the ground from foraged plant debris. Eggs hatch in a month and chicks fledge in two months.

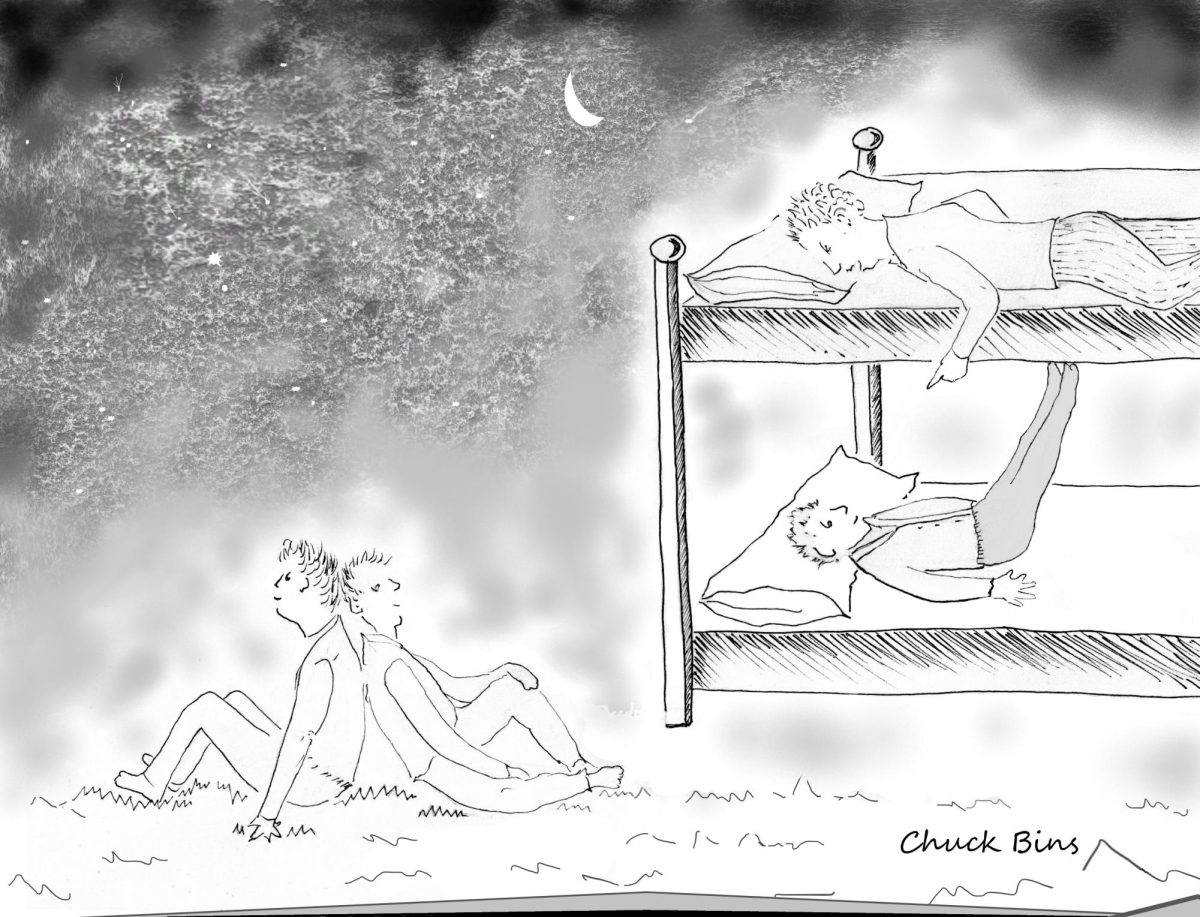

The cranes’ trip south begins in autumn with their offspring, who will mature in two years, seeking their own mates. Some flocks of sandhill cranes make their way south along the Front Range area of the Rocky Mountains, following the South Platte River close to the Denver metropolitan area before they head south to Arizona and New Mexico. When resting, feeding or flying, these cranes are a delight to birdwatchers and photographers. Mating dances of sandhill cranes provide a distinctive show, with wing flapping, leaping, and bowing or other antics displaying their artistic courting maneuvers, sometimes performed year-round. The sandhill cranes mate for life. If one mate dies, the other seeks a new mate. The loud mating call is a bugle-like rattle “carrrrrrooooo” sound, one note sung by the male and two notes sung by the female.

The lifespan of sandhill cranes can be 20 years or more, but chances of dying young are greater for those living in the wild due to loss of habitat and wetlands. Climate change and land development pose a treat, with two subspecies currently on the federal endangered species list. Cranes are one of the world’s most stately and noble birds, known for their strength, ability to migrate long distances, hunting prowess, and wisdom. Celt warriors were known to have adorned their shields and armor with images of cranes. It was considered a good omen if a crane crossed your path, keeping you safe and secure. We must now help keep the cranes safe and secure.

I was fortunate to observe these magnificent, impressive birds while I fished from a boat on a Colorado Front Range lake and again while cranes fed in wetlands of southeastern Arizona. Sandhill cranes can be a noisy bunch, having sophisticated communication skills to signal danger or to maintain family unity. The flight of a huge flock overhead almost blots out the sun, casting dark shadows and making the sunlit day momentarily seem like evening. I observed their graceful landing, one after another, and their elegant dance on their long, slim legs. Sandhill cranes – beautiful ballerina birds.

Susana • Jan 8, 2025 at 9:57 am

So beautifully described. I yearn to see & hear them much more often here along the Gulf of Mexico in Texas. Their sounds touch my soul deeply. Thank you for sharing your detailed experiences so well.

Angela Westmoreland • Jan 8, 2025 at 9:34 am

There are 2 that visit me often…also in Florida

Kris Bennett • Jan 7, 2025 at 7:52 pm

They are truly amazing! I love watching them dance. I have a pair that visit in Wisconsin each summer…they are usually around mid July thru late September.

Ralph Rafael Rodriguez • Jan 7, 2025 at 10:32 am

What do you do,when you see a sandhill crane with a broken leg? Who can assist them? I called animal rescue..nothing they can do. Deltona,Florida.

Linda L • Jan 5, 2025 at 10:17 pm

They walk by my house all the time! Florida.

John B Lester • Jan 8, 2025 at 10:50 am

I am jealous