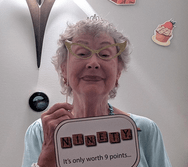

My mother turns 90 on September 14th, but to accommodate the working schedules of several children and grandchildren, we held a week-long birthday celebration for her at the end of July. One night featured a party with catered food, music, and a signature drink—the IRMA-nhattan—a play on her name “Irma” and her favorite adult beverage. The grandchildren put on a skit—Super G’ma—which involved my mother saving her adult children from the evil Mr. C (short for COVID). The “Super G’ma” skit is a tradition that started 15 years ago; it gets rewritten and performed at every five-year milestone in recognition of my mother’s indefatigable spirit.

Born in the early 1930s to German immigrants, Irma Eisele had to grow up fast when, at seven, her mother died of tuberculosis. Her father was a “Messerschmied” or cutler who worked six or seven days a week to provide for his young family in a small, two-bedroom apartment in the Bronx. When his wife passed away, he put my mother in a Catholic orphanage for several weeks until German friends stepped in to watch her after school.

Born in the early 1930s to German immigrants, Irma Eisele had to grow up fast when, at seven, her mother died of tuberculosis. Her father was a “Messerschmied” or cutler who worked six or seven days a week to provide for his young family in a small, two-bedroom apartment in the Bronx. When his wife passed away, he put my mother in a Catholic orphanage for several weeks until German friends stepped in to watch her after school.

They later moved to a nicer section of the Bronx, where many of her friends had single-family homes and several siblings. It was, she said later, all she wanted in life—a nice home and family. And so it came to be. After she married, my mother quit her secretarial job in the city and settled with my father in a small brick house on Long Island. Along with her three children, this became my mother’s primary focus for the next 35 years.

To my recollection, my mother was constantly cleaning, ironing, or dusting. I can still see her bending over the tub, scrubbing it out each weekend. She rarely sat down, often eating lunch on her feet. Sometimes she would vacuum around us while we tried to watch TV. Being an extrovert, she needed some activity outside the house, so she joined the elementary school PTA—first as Secretary (I remember printing newsletters on a mimeograph machine in our basement), then as President. Years later, she found her intellectual stimulation working part-time at an advertising agency.

After my father retired, my parents moved to Lake Monticello, just outside of Charlottesville, VA. When my father died of cancer four years later, my mother became more immersed in the community. She served on the local beautification committee, took adult education courses at UVA, and helped to establish a new Lutheran church. Before she moved to join us in North Carolina, the church held a farewell party in her honor, at which person after person sang her praises. Her grandchildren call her the “spunky” grandma. She was the only grandparent who stayed up past dinner at my son’s wedding, switching out her heels for sparkly flats and dancing till the band stopped.

In the last decade, my mother channeled her energy towards political and social activism. Back on Lake Monticello, she canvassed for the Democratic Party and helped find homes for sheltered cats. Since moving to the Cape Fear region, she has protested at the Women’s March in Wilmington and rallied in Raleigh against offshore drilling. A clear and focused writer, she has published over 25 letters-to-the-editor in the StarNews. Had she been born a generation or two later, her gift of rhetorical persuasion would have made her a great lawyer.

In the last decade, my mother channeled her energy towards political and social activism. Back on Lake Monticello, she canvassed for the Democratic Party and helped find homes for sheltered cats. Since moving to the Cape Fear region, she has protested at the Women’s March in Wilmington and rallied in Raleigh against offshore drilling. A clear and focused writer, she has published over 25 letters-to-the-editor in the StarNews. Had she been born a generation or two later, her gift of rhetorical persuasion would have made her a great lawyer.

My mother still lives independently, does water aerobics, and drives a car. Her house continues to be immaculate, and she has the prettiest garden on the street. She has never had a serious disease or an injury requiring overnight hospitalization. But arthritis is slowing her down, and a month ago, she finally hired a woman to help clean. And after her party, she shared with us that she has had a good, long life and that “if she died tomorrow, it would be okay.” But that is not likely to happen any time soon. The way she is going, my mother will live to 100. Super G’ma will outlive us all.