Laughing in the Golden Years: Monkey Business

One year before WWII began, my dad invited me to the city to pick up some car parts to repair our old Ford, which he had purchased used. Dad said that if I were quiet and well-behaved while he shopped, he would take me to see something really special. He explained it is something that most likely will not be around when you are grown.

Once in the city, dad parked and taking me by the hand, went into Genesee Supply – yesterday’s answer to Advance Auto. I sat on a stool at the counter while dad “chewed the fat” with the men who waited on him. One of the clerks gave me a lollipop, and I sat quietly listening. I was probably about four years old, but I learned early to be still and quiet when grownups talked.

I learned a lot of fascinating things by looking as though I wasn’t interested. At any rate, I heard dad say that he was taking me to see a monkey. Since there was no zoo at that time in the city, I wondered where there would be a monkey. I could hardly wait to get going, but I knew better than to interrupt because my dad was strict about me getting in the way of his conversations. After a while, he finished and lifting me down from where I was sitting. We went out to the car and drove to what was then the theater district. Dad parked the car on a side street with no parking meters because he hated to pay for parking no matter how important it was.

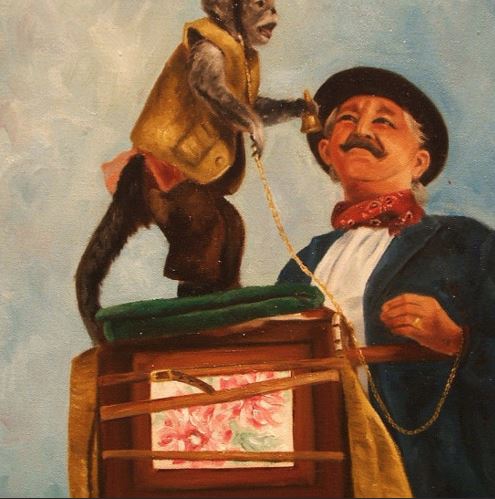

Taking me by the hand, he led me up the street and around the corner. Before long, I began to hear music, kind of jazzy but slightly tinny. Then I saw it – a man with a box on a strap over his shoulder turning a handle which was making music. Dad said the man was called an organ grinder. To my delight, he had a leash with a tiny monkey at the end of it dancing in rhythm to the music. Once I saw the monkey, I didn’t notice anything else. I remember that the organ grinder had a very long mustache that hung below his chin. After that, I only had eyes for the monkey. He was wearing a little red jacket with gold trim and a tiny box hat on his head. Dad gave me a nickel, and when the monkey stopped dancing, dad said to put the nickel in the cup, which the monkey was waving around. When I dropped the money in the tin cup, the monkey snatched it out and put it in a pocket on his jacket.

Immediately the organ grinder said, “No, no! Give me the nickel.” The monkey looked at him and shook his head no. “What will I do to you if you don’t give me that nickel?” the organ grinder asked. Immediately the monkey turned his back to us and, lifting his tiny behind upward, spanked himself. I laughed and then asked my father if we could buy the monkey.

My dad shook his head and said, “The organ grinder needs him, and besides, your mom would have a fit if we brought a monkey home.” I knew that was for sure, so I didn’t ask again. But I surely believed that the little monkey was as smart as any monkey could ever be.

About two years later, my first-grade teacher was getting us ready to read a story about a monkey and asked, “Can monkeys talk?” The kids in my class said, “No!” but I said, “Yes, monkeys can talk.” Miss Walsh, my teacher, said, “No, Maryann, monkeys cannot talk.” I stood my ground and said again, “Yes, they can so talk!”

She just shook her head at me, but that wasn’t the end of it. As soon as I got home that afternoon, my mom greeted me with, “What on earth makes you think a monkey can talk?” I knew then that Miss Walsh had called my mom. When I explained about the organ grinder’s monkey, mom said, “That monkey could follow directions just like our dog does, but neither one of them can speak words.”

I knew better than to argue with my mom; I continued to believe that the organ grinder’s monkey could talk, but I sure didn’t say that to my mother as her word was law. It was a long time before I learned about passive language, and I understood the monkey’s actions. I have always kind of believed that the smart little monkey could talk. After all, wasn’t shaking his head at the organ grinder a way of speaking?