When I was twelve, I went to work on a farm picking beans alongside of migrant workers. I had never before seen a person of color and I must admit that I was frightened of the African American women and teenagers who were working there. Still, I had picked beans in my mom’s garden for years and I wanted the money I could earn.

My mother packed a lunch for me and told me to be very careful when I rode my bike to the farm. When I arrived at the field, an old man gave me a bushel basket and showed me a row of beans that was assigned to me.

I picked beans as quickly as I could, but I soon became aware that the other pickers were carrying their baskets to a wagon at the end of the field, dumping them and returning to dump a second basket, when I had not even filled my basket once. A few rows over a black teenage boy, about 14 years old, called something to me, but I could not understand his thick southern accent. He jumped over the rows and kneeling down beside me, took my basket and dumped my beans on the ground. I was horrified and demanded to know what he thought he was doing. Soon I understood as he picked up my beans a few at a time and systematically crisscrossed them, and to my surprise my basket was full. Then I understood that he had asked, “Do you want me to show you how to pick?” But what I heard was, “Yo wan me sho yo how pik?”

Pointing at the wagon where other pickers were dumping their baskets, he said, “Go!” and I ran. The old man supervising the dumping of the baskets pointed to the wagon, and I proudly dumped my basket. He gave me a green ticket and cautioning me not to lose it, saying the ticket was worth ten cents.

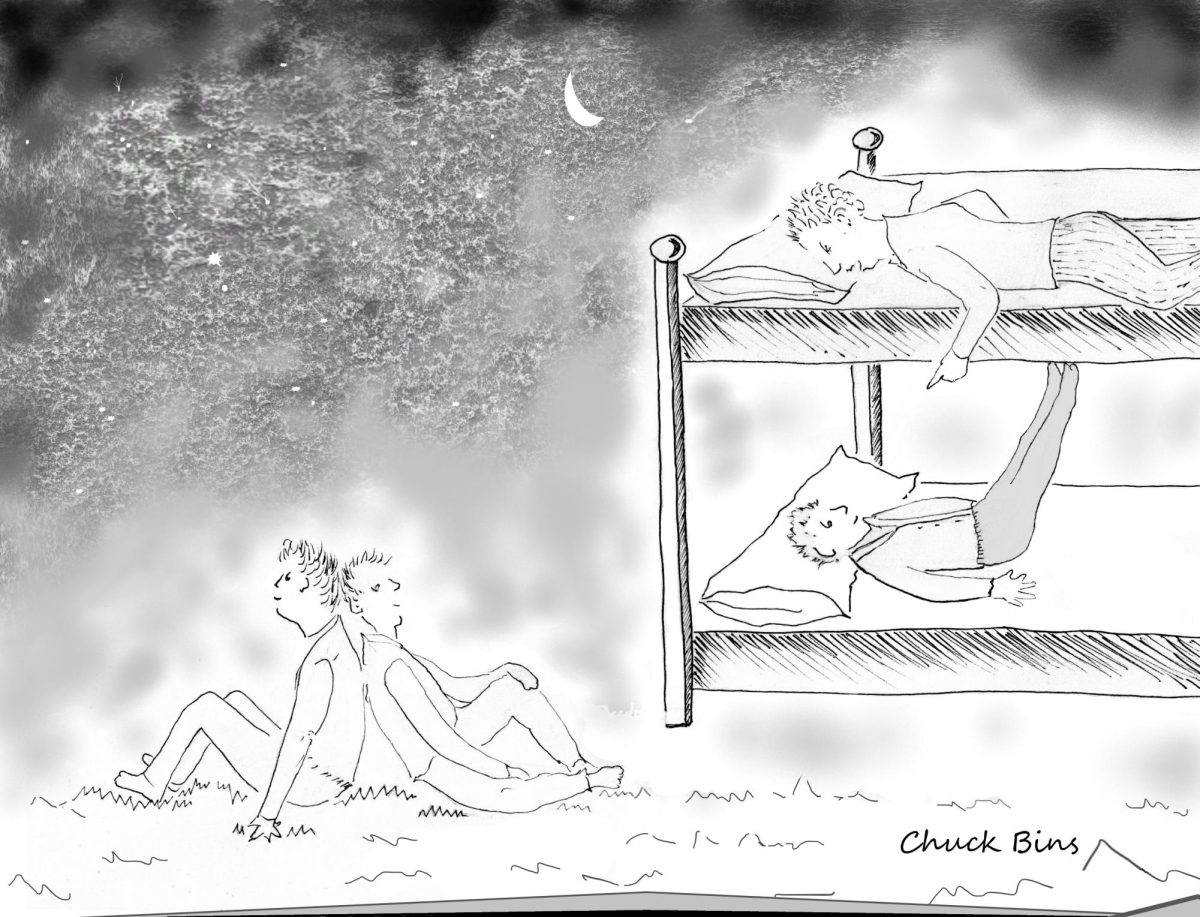

When I returned to my row the boy was waiting for me and for the rest of the morning we picked together.

At lunch time all the women went into the nearby woods to use as a bathroom. Fortunately, my mom had packed a wet cloth and some tissue in my lunch box, so I was much better off than the migrant women.

My new friend joined me under a maple tree. When I opened my lunch box, he stared at my thick ham sandwich, huge piece of berry pie and the thermos full of cold milk. “Wanna swop?” he asked. Then he handed me his brown greasy bag and bottle of orange soda and helped himself to my sandwich and milk.

I have had some wonderful meals, but that bag of something greasy, salty and crispy was the most delicious food I have ever tasted. The orange soda was a delicacy for me as my mother would never allow soda of any kind in our house. Oh, how I loved that lunch.

I waited each day to trade lunches with Robert Lincoln Jones, as I found what his name was. Mother would have been appalled had she seen what I was eating and drinking, but she was delighted that I was eating everything she packed for me. She didn’t have an inkling that I was eating junk, while Robert was devouring my healthy lunches. Robert and I were a team, and each day meant we learned more about each other. I think he must have found it very strange to talk and eat with a white girl. But truthfully no one paid the least bit of attention to us.

At the end of the week the field was picked out and on the last morning a rickety bus arrived to pick up the migrant workers. “Could we write to each other,” I asked Robert. “Girl,” he answered, “I caint write. I ain’t never been to no school.” I stood there crying as the bus pulled out. Over the years, I have wondered what ever happened to him. He was, as the kids say today my BFF for that one short week, and I will always be grateful that I met him.

As retired educator, I now realize what an impact Robert Lincoln Jones had on my life. Often, I chose to work with students who had had very little schooling, and I took up the challenge to make sure that they could read and write when they left my classroom. Because of Robert Lincoln Jones, I had a fabulous career and got up every morning thrilled to go to work and seeing in every face before me, my BFF, Robert Lincoln Jones.