The Agony and the Ecstasy Part 1

September 28, 2022

The Agony and the Ecstasy (Part I)

by Janet Stiegler

If you ever travel to Italy, particularly Rome and Florence, I recommend reading Irving Stone’s biographical novel of Michelangelo, The Agony and the Ecstasy. Published in 1961, the book is divided into eleven sections, each detailing a distinct period of the artist’s life. Stone based much of the novel on a translation of Michelangelo’s 495 letters, and it is hard not to become absorbed in the artist’s journey.

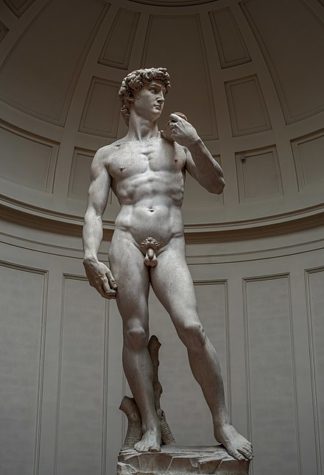

Although Michelangelo was a Renaissance sculptor, painter, architect, and poet, he considered himself, first and foremost, a sculptor. He sculpted two of his best-known works, the Pieta and David, before age 30. Because there would not be room to cover all of Michelangelo’s works here, I will focus today on the artist’s love of sculpture and his creation of David, as portrayed in Stone’s novel. Also, the author spent several years working in Tuscany’s marble quarries and apprenticed himself to a marble sculptor. By the end of the first chapter, you will be tempted to pick up a hammer and chisel yourself.

Michelangelo first gained his love of marble at age six when he lived with a stonecutting family on the outskirts of Florence. The Topolinos taught him to work the stone with love, “to seek its natural forms, its mountains and valleys. The scalpellini respected stone…and handled it with reverence.” In a subsequent chapter, when Michelangelo is living and working in the Medici palace, the author describes the young artist digging into a block of marble in terms we usually associate with lovemaking.

Michelangelo was particularly fascinated by the naked male body, and he dissected cadavers to understand better how the human body’s muscles and tendons worked. In the novel, he claims to a friend, “I find all beauty and structural power in the male. Take a man in any action, jumping, wrestling, throwing a spear, plowing, bend him into any position, and the muscles, the distribution of weight and tension have their symmetry.” Some art historians have noted that, while Michelangelo did paint and sculpt women, their bodies tended to be masculine.

David: Stone devotes an entire chapter to Michelangelo’s creation of David, otherwise known as “The Giant.” Michelangelo was asked to complete an unfinished project begun 40 years earlier—a colossal statue of Carrara marble portraying the biblical David. The first sculptor left a deep gouge in the marble, and Michelangelo had to approach the project as both an engineer and an artist. “Tilting the figure twenty degrees inside the column, he designed it diagonally, down the thickness of the marble…so that his David would never [collapse].”

Stone also spends pages detailing Michelangelo’s search for the emotion he wants his David to reflect. After studying several other sculptures of David in the city, including that of the great Donatello, he determines that they are all too boyish or feminine. He asks himself, “When did David become a giant? After killing Goliath? Or at the moment he decided he must try? According to Stone’s portrayal, Michelangelo felt that “the decision was more important than the act itself since character was more critical than action.” Hence, David’s right hand, bulging with veins, encloses the stone, the cords in his neck are pulled taut by his head turned towards Goliath. “He was not content to portray one man: he was seeking universal man. Everyman, all of whom, from the beginning of time, had faced a decision to strike for freedom.”